The audio version of the essay remains on hiatus this week as Dr. Horner continues his series of Advent meditations.

In proposing that we use Paul’s comment about gaining “the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ,” as a framework for reading the gospels, and specifically for reflecting on the experience of those who looked into the infant’s face, I suggested that we ask three simple questions. First, What did they see? Second, What did they understand? And third, What did they struggle to understand?

The answer to the first question is straightforward enough and relatively easy to answer. Mary and Joseph, the shepherds, the angels, and any random stranger, who happened to stick his head in the door to see if everybody was okay, all saw the same thing: a newborn baby boy. He looked pretty much like any other little Jewish male infant. No reason to think of him as anything unusual.

The questions about what these onlookers understood and what they struggled to understand, however, are not so easily answered. Consider, for instance, what his mother Mary understood and what she struggled to understand. As Mary gazed into that little face, she understood better than anyone that her little baby was exactly that—a little baby. She had just given birth to him. She knew he was the genuine article. She knew this much to be obvious and true. There were inexplicable mysteries surrounding her son’s conception, but the baby himself was clearly the real article. He was a little boy—her little boy, and he was as needy and dependent on his mother as any other little baby born before or since.

What Mary struggled to understand was what else he was. Given the mysterious and miraculous nature of the conception of this child, she knew he was something more. According to Luke’s account, she knew that his name was to be Jesus, which Matthew explains to us implies that he was to be a Savior. Mary also knew that her son would be great, that he would be called the Son of the Most High, and that the Lord God would give him the throne of his father David—forever! Most remarkably, while the conception would always remain a mystery to her, she knew that the Holy Spirit had come upon her, that the power of the Most High had overshadowed her, and that her child would not only be called son of Mary but Son of God. Her son would be God’s Son. But “Son of God”—what could that possibly mean?

Putting the pieces together: the words of the angel Gabriel; private, tearful talks with her husband; conversations with her cousins Elizabeth and Zechariah; a visit from some shepherds who had their own amazing story to tell, she pondered. She wondered and tried to imagine what it all meant. She gazed into her baby’s face as she nursed him and wondered what it could mean that she was looking into the face of the Son of God, Immanuel, God with us. How could it be, as her cousin Elizabeth had stated so bluntly, that Mary had become the mother of her Lord.

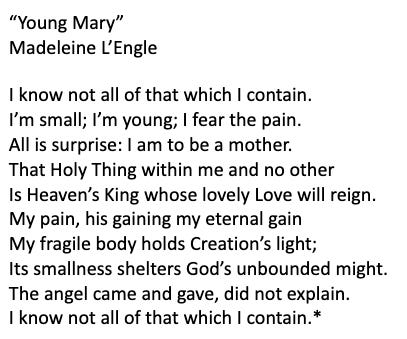

As Madeleine L’Engle has “Young Mary” admit, “I know not all of that which I contain…. All is surprise: I am to be a mother.” But she ventures, “That Holy Thing within me and no other Is Heaven’s King whose lovely Love will reign…. My fragile body holds Creation’s light; Its smallness shelters God’s unbounded might.” But then, Mary reaches the limits of imagination. “The angel came and gave, did not explain,” she tell us, and then she concludes as she began: “I know not all of that which I contain.”

Luci Shaw writes with similar insight and imagination. With Mary, she ponders these things in her heart and contemplates what it means for the Word to be “Made Flesh.”

After the bright beam of hot annunciation

Fused heaven with dark earth

His searing sharply-focused light

Went out for a while

Eclipsed in amniotic gloom:

His cool immensity of splendor

His universal grace

Small-folded in a warm dim

Female space—

The Word stern-sentenced to be nine months dumb—

Infinity walled in a womb

Until the next enormity—the Mighty,

After submission to a woman’s pains

Helpless on a barn-bare floor

First-tasting bitter earth.*

The Light of Heaven “eclipsed in amniotic gloom.” “The immensity of splendor … small folded in a warm dim Female space…. Infinity walled in a womb.”

The glory of God in the face of a fetus.

But wherein does that glory finally lie?

Certainly, it lies in the miracle of the conception, but even more it lies in the way that the baby Jesus reveals the character of God. What sort of God are we talking about who subjects himself to amniotic gloom? What sort of God humbles himself this way? The very thought of God being humble sounds odd, if not simply wrong, and yet this is exactly what we are dealing with. He is a God who humbles himself and who loves the humble.

As Mary herself put it early in her pregnancy, the Lord God “scatters those who are proud in their inmost thoughts,” but he lifts up the humble. “My soul glorifies the Lord,” she says to her cousin, “and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior, for he has been mindful of the humble state of his servant.” (Luke 1.46-48, 51-52) Like the angels and shepherds, Mary responds to the glory of God by giving him glory, and as she does so she delights in the humble character of a God who is mindful of the humble and lifts them up.

Humility is not a static quality. It is a choice, and in Jesus, God made this choice. He humbled himself by becoming one of us, and he humbled himself still more by becoming one of us in the way that he did. The infinite, eternal Word of God, by whom all things are created, rendered himself mute, “stern-sentenced to be nine months dumb. Infinity walled in a womb.” This is the humility of the Son of God. This is the glory of God in the face of Christ. Mary saw it up close and very personally and pondered it in her heart.

“May it be to me as you have said,” Mary says to the angel, and then she “glorifies the Lord” as she reflects on the blessings that are about to be poured out through her son. She provides an example for us all, and in the second stanza of “Made Flesh,” Luci Shaw captures this as well. I am once again glad to borrow words from one who wields them well.

Now, I in him surrender

To the crush and cry of birth.

Because eternity

Was closeted in time

He is my open door

To forever.

From his imprisonment my freedoms grow,

Find wings.

Part of his body, I transcend this flesh.

From his sweet silence my mouth sings.

Out of his dark I glow.

My life, as his,

Slips through death’s mesh,

Time’s bars,

Joins hands with heaven,

Speaks with stars.*

*Highly recommended sources for Madeleine L’Engle’s and Luci Shaw’s poetry include:

Madeleine L'Engle and Luci Shaw, Winter Song: Christmas Readings (Regent College Publishing, 2004), and Luci Shaw, editor, A Widening Light: Poems of the Incarnation (Regent College Publishing, 1997).